Or, the house where Grant never actually lived.

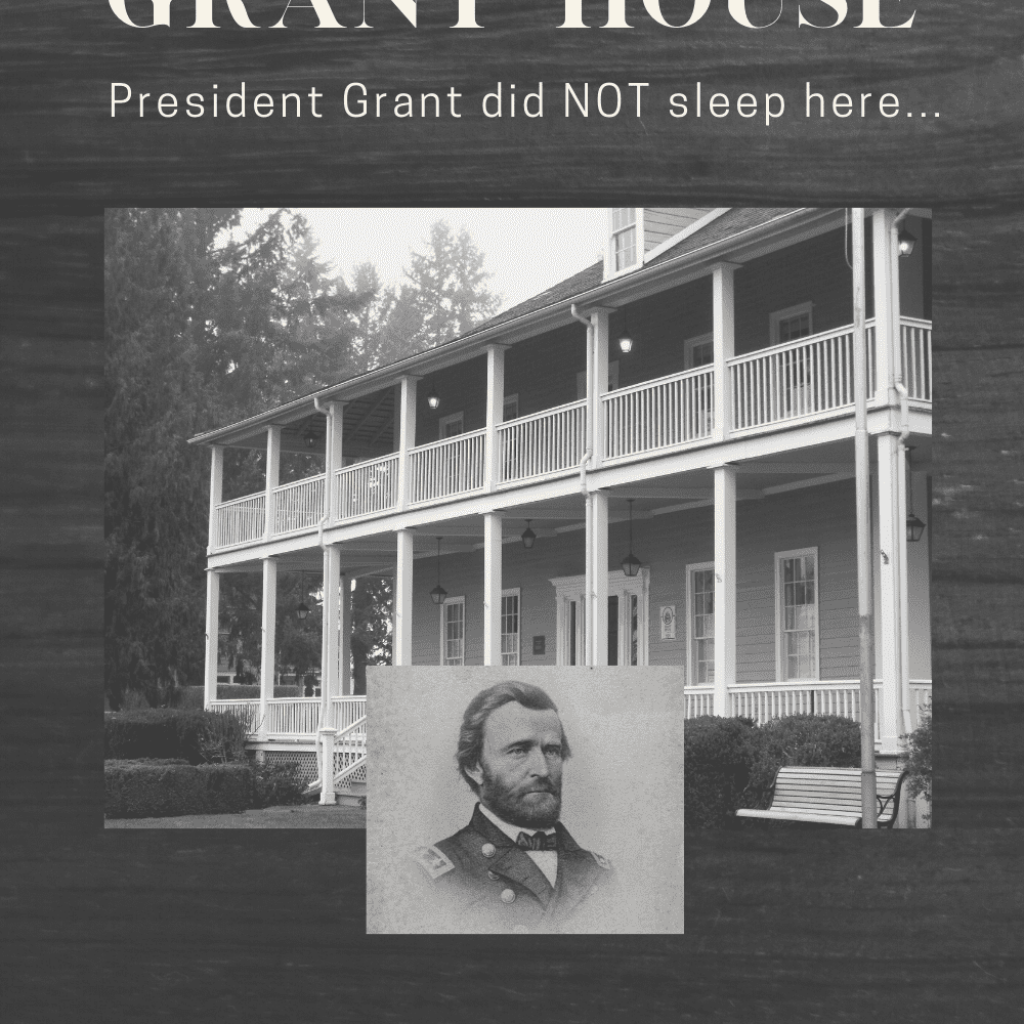

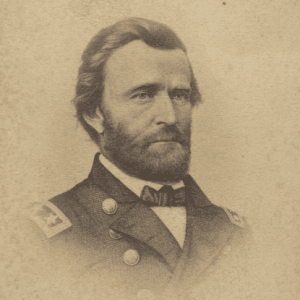

How would you like to have a house named after you – despite the fact that you never actually lived there? Funny story… they named a house in Vancouver, Washington after a man who never lived there. It is more honorary than historical. Although President Ulysses S. Grant did work in the vicinity, and probably did set foot inside.

Now dubbed the Grant House, the elegant old house sits along a long, straight, tree-lined street facing the former parade grounds on Fort Vancouver just a short distance from the Columbia River banks. Like soldiers in formation, the long line of beautiful old homes sit shoulder to shoulder along what was once named Grant Street. They tell a story of times long past, when Vancouver was the home of the Department of the Columbia, and eventually Fort Vancouver.

The house was built in 1849 for use as headquarters and as commanding officer living quarters as soon as the army arrived. It is the oldest standing building on the Vancouver Barracks site. Originally just a square home built of hand-hewn logs, clapboard siding was added to keep out the cold winds and double-level exterior porches were added, wrapping three-fourths around the building, almost doubling the size of useable space. Once the verandas were added, the house has changed little over the years. If it wasn’t his house, why is it called Grant House?

Ulysses Grant was 30 years old when he arrived in Vancouver as a Brevet Captain in the army and stationed here with the 4th Infantry in 1852. He was assigned to work out of the Quartermaster’s office, which is where he both lived and worked. He had previously been quartermaster during the Mexican-American war, efficiently overseeing the movement of supplies. His time at the Vancouver Barracks was not a happy time for Grant in his life – he did not love the military life. He had attended West Point military academy as the best option to get him out of having to work at his father’s tannery back in Ohio. Now newly married, his wife and two young children were back home in St. Louis, and Grant struggled to earn enough money to get them out west to be with him.

“The fact is my dear wife,” he wrote Julia,

“that if you and our little boys were here I should not want to leave here

for some years to come. My fears now however are that I may be promoted

to some company away from here before I am ready to go.”

He liked the area and had hopes to begin a new life here with his family. He enjoyed farming and leased a 100-acre farm about a mile from the post, where he and several fellow officers grew potatoes, onions, corn, barley, and oats. The farm was unfortunately flooded and the entire crop was ruined. He tried several other fundraising schemes, all of which failed. He began to drink – a common problem with many who were posted at Vancouver Barracks, and an issue that tarnished his reputation for years. Grant himself was only in Vancouver a year before being promoted to Captain in the summer of 1853 and posted to Fort Humbolt in Northern California. By 1854 he had resigned from the army to return to St. Louis.

It took the firing on Fort Sumter and the flames of the American Civil War to bring him back into the army. He never did like military life, but his experience and exemplary horsemanship skills were of great use and would take him to the highest ranks even he could not have expected. Many of the soldiers he knew from his days at Vancouver Barracks would become both trusted compatriots or adversaries in the war to come including Union Generals Benjamin Alvord, Benjamin Bonneville, Henry C. Hodges, Rufus Ingalls, George McClellan, Augustus V. Kautz, Phil Kearney, Alfred Pleasonton, Joshua W. Sill, and George Wright. Officers who served at Fort Vancouver and became Confederate generals were George B. Crittenden, William Wing Loring, Nathan Wickliffe, Gabriel J. Rains, and George Pickett.

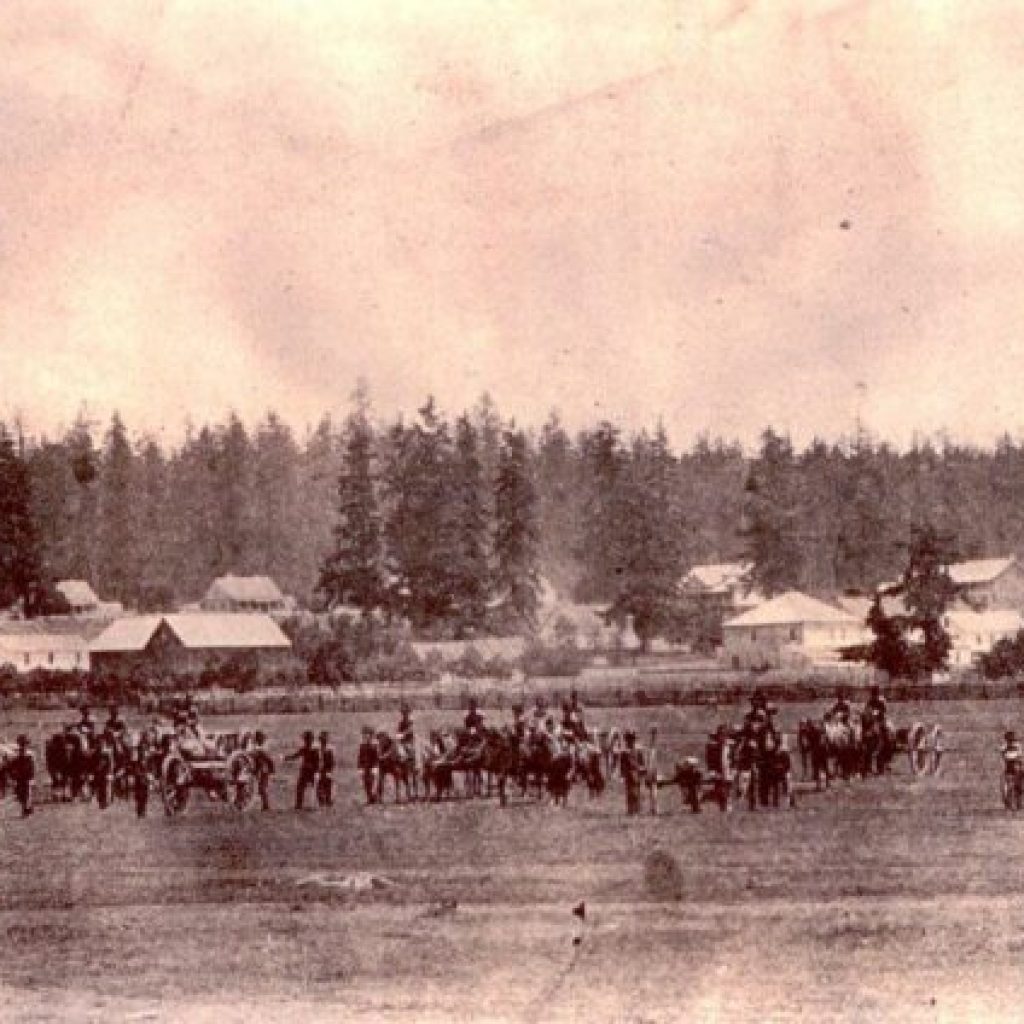

After the Civil War, Grant remained in the East, while military activities in the West were on the rise due to ever increasing conflicts between Native Americans and settlers arriving on the Oregon Trail. Vancouver Barracks became the Headquarters of the Department of the Columbia, which encompassed the immense territory of Oregon, Washington, Alaska and portions of Idaho territories.

Grant returned to Vancouver in October 1879, now a former two-term President of the United States of America, accompanied by his wife and son. His visit was highly publicized, and following the visit, the Post Headquarters was officially renamed the Grant House.

The house remained as the Headquarters until 1886, when a reorganization changed it to become quarters for commissioned officers and an officer’s mess club while the Post Commander was moved to the O.O. Howard House, just a few houses down the street. It remained as an officer’s mess club until 1930 when it was changed again to be used as Non-Commissioned Officer Bachelor Quarters. A few years later it became the Post library, then back to Bachelor Quarters until the end of World War II. By 1974, the buildings were showing their age and deemed too expensive to heat and maintain. In a desire to save the historic site, the homes on Officer’s Row were added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1980 the City of Vancouver acquired all of the Officer’s Row houses and maintains them today.

The Grant House, with its officer’s mess kitchen facilities, was revamped into an elegant restaurant – keeping as much as the original character and layout as possible. A small bar fills one of the downstairs rooms, a dining room with dark wood paneling and fireplace fill another, and a light and airy breakfast room fills the third downstairs room. Outdoor dining on the veranda is an elegant way to enjoy a summer’s evening or a sunny lunch overlooking the old barracks buildings and parade grounds. Although the street in front of the Grant House has been paved and renamed Evergreen Boulevard, the elegant tree-lined street once would have been filled with the sounds of soldiers on horseback. It is not too hard to visualize Civil War era troops of the 4th Infantry practicing their drills on the lawn out front, a WW1 era camp filled with tents, or WW2 era jeeps buzzing by. The annual Veteran’s Day Parade is held on the grounds and is an elegant and appropriate location to enjoy the parade when those old jeeps and soldiers on horseback visit once again.

War has a way of changing destinies. For Ulysses Grant, he never did realize his dream of living in the Northwest with his wife and children, perhaps on a nice farm where he could live a peaceful life. Instead, history had other plans for him. He became a two-term president of the United States with numerous streets, parks, schools, and even houses named after him. For although he did not live in the Grant House, he deserves the honorary title for having served his country well.

Visit Officer’s Row at Fort Vancouver National Historic Park on a cruise stopping in Portland/Vancouver on the Columbia River:

Columbia & Snake Rivers Cruise – American West

Portland to Clarkston

- 8 Nights

- April 16, 2025,April 23, 2025,May 4, 2025--

23 more dates available. - From $5,145

- American West

Save this story to Pinterest