Why George Washington Owned a Piece of French History

by Dawn Woolcott

Why would the newly minted first President of the United States have a piece of the French Revolution hanging in his front hallway? This new found country seems an unlikely place to find the key to the French Revolution. Yet in a very literal sense of the word, it is.

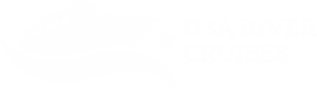

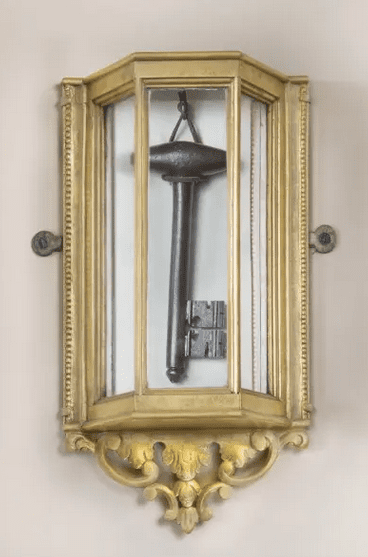

Inside an easily missed, elegantly designed little box hanging on the wall inside the hallway of Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home in Virginia, you will find a large metal key. It looks fairly old, because it is. The key is to the Bastille, the notorious medieval fortress that dominated the city of Paris for centuries. Built with 100 foot high stone walls and 8 guard towers, the massive fortress had long been a site of intimidation and power. Built in 1370, the Bastille now held political prisoners and had become a symbol of the cursed aristocracy and their power over common citizens. One Frenchman offered up the key to this intimidating fortress to the newly elected President of the United States who himself had just fought a mighty aristocracy and won.

The Frenchman was no one other than the Marquis de Lafayette, whose storied life and career intersected with George Washington in a most crucial way. The Marquis was born Gilbert du Motier and inherited the title of Marquis de Lafayette upon the death of his grandfather, who had raised him after his father had died in battle against the British. The death of his father left Gilbert with no great love of the British. Although born into aristocracy himself, he was drawn to the fight the colonists were waging against the British and wanted to help in the war. Against his family’s wishes, the 19 year old purchased a ship himself and sailed across the Atlantic to offer up his services. Following the 56 day voyage, he arrived in South Carolina and made his way up to Philadelphia. At first rebuffed by the army who thought he was just a “glory seeker,” no less than Benjamin Franklin himself wrote a recommendation on Lafayette’s behalf and in1777 managed to get him assigned to a prime post – as an aide-de-camp in General George Washington’s army. The Marquis and General Washington quickly formed an excellent working relationship.

Washington grew to trust his judgment and relied on him in several key battles. Working without pay, the Marquis actually paid the equivalent of approximately $200,000 for uniforms, aides, equipment, and supplies in order to serve. Within a month of signing on, the Marquis was in battle. From the Battle of Brandywine, to chasing down the defector Benedict Arnold, to the climactic battle at Yorktown when the British surrendered, the Marquis de Lafayette was there. By the end of the war, George Washington considered him his “French son.”

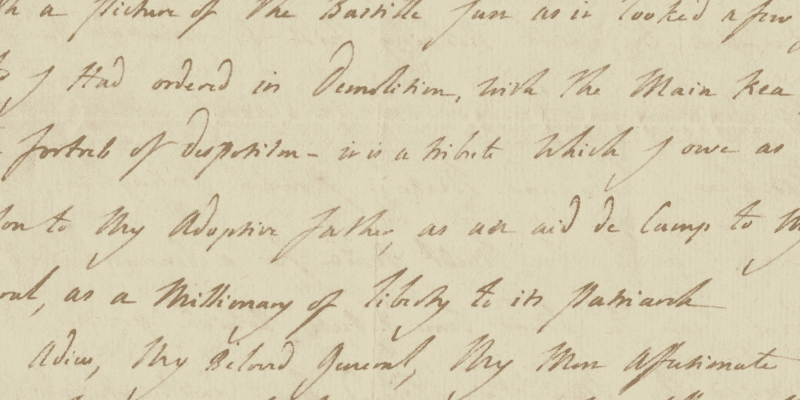

Following the American Revolutionary War, the Marquis returned to France, where tensions were rising against the aristocracy. The Marquis helped forge trade agreements between the United States and France. He worked from within to promote democracy and the abolishment of monarchy in France. In July 1789, the revolution in France was underway when the Bastille was stormed by the “commoners” who overtook the prison, an event today that is celebrated as Bastille Day, or the French day of independence. Once the Bastille fell, the now 32 year old Marquis was placed as head of the local National Guard. One of his first acts was to raze the Bastille. The Marquis took possession of the key and prepared it to ship to his friend, George Washington. There is nothing left of the fortress today – it was completely wiped off the face of the city. During the next month, the Marquis helped write the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, which did not do him any favors in the eyes of the king. The Marquis fled the city, but was captured by the Austrians. Sitting in prison no doubt saved his life, as if he had remained in Paris, he would most certainly would have been executed along with the other aristocracy.

By 1793 the Royal family had left the city of Paris and by 1794 they had been executed. After a few turbulent years, Napoleon Bonaparte was in power and the Marquis tried to keep a fairly low profile, although he argued for Napoleon’s abdication following the loss at Waterloo. Yet it was Bonaparte who had the Marquis released from prison in 1797.

After years of fighting for a balanced form of government on two different continents, the Marquis was eventually offered positions of importance but declined them both, opting to retire to become a gentleman farmer. In 1803, Thomas Jeffereson offered to make him governor of the newly formed Louisiana Territory and later in 1830 following the abdication of King Charles X in France, he was offered the chance to lead a coup and seize control of the government, but declined both. He was however, the first person to ever be granted Honorary Citizenship in the United States.

The key made its way from turbulent France to the calmer waters of America, entrusted to Thomas Paine to help with delivery. The honor of placing the key in the hands of George Washington fell to John Rutledge, Jr., a South Carolinian who was returning to the United States from London. The key was on display in Philadelphia where the young country’s new government was based. It was not until George Washington’s retirement in 1797 that it went with him to Mount Vernon. The wrought iron key in its display box was hung in the first floor passage. There it has remained, even after George Washington’s passing two years later, and for the next 3 generations of the family until the property was sold to the Mount Vernon Ladies Association for keeping as a museum.

The President is buried at his beloved Mount Vernon. The Marquis himself traveled there in 1824 with his son, whom he had named George Washington Lafayette. They paid their respects at the tomb of the man whom he regarded as his adoptive father. He no doubt saw the key hanging there on the wall unchanged after all those years. This symbol of friendship and of democracy – the last piece of a demolished prison that was an emblem of cruelty and the fight for the rights of the common man. Both countries suffered in those turbulent years in the late 18th century, yet arose better for it. These two amazing men fought the good fight – not for personal glory, but for the good of humankind. Their life-long friendship is represented in one lone key hanging on a wall, the same today as it has for over two centuries, much as George Washington and Gilbert du Motierthe would have liked it.

Their friendship, and the friendship that has continued between France and the United States, is celebrated with a statue in Lafayette Square in New York City. You can also see the key on display at Mount Vernon and pay your respects to the man who would not be king – who, like the Marquis de Lafayette, just wanted to be a gentleman farmer.

You can visit Mount Vernon on a history-filled cruise on the Chesapeake Bay:

Save this story to Pinterest: