The Columbia River covers 1,243 miles as it winds its way through the beautiful Pacific Northwest. The river’s headwaters are in Columbia Lake, nestled in the Canadian Rocky Mountains of British Columbia. After a nearly 180-degree bend in B.C. it heads south through Washington, then splits Washington and Oregon before emptying into the Pacific Ocean. On a Columbia River cruise, you pass along the Columbia past historical hydroelectric dams, picturesque settlements, and awe-inspiring rock formations, only then do you realize just how breathtaking the Northwest region is. It’s one of America’s most treasured lands, yet it also remains one of the country’s best kept travel secrets. Take a cruise aboard your choice of traditional paddlewheeler or a modern river boat available on the American West, American Empress, American Pride, American Song , National Geographic Sea Lion, American Jazz, National Geographic Sea Bird, or American Harmony and take in everything the Columbia River has to offer.

The former Queen of the West docked in the majestic Columbia River Gorge has now been renamed The American West

Early Columbia River Explorers:

As settlers moved across and sailed around the North American continent in the mid-18th century, many were hoping for a NW passage; a river than might connect the Pacific to the Hudson Bay or at least the Missouri River. But, since so many explorers had looked and never found the mouth of the river, it seemed it didn’t exist. In fact, in 1788 British captain John Meares very narrowly missed it, naming Cape Disappointment for his woes, which ironically was the north edge of the river’s mouth.

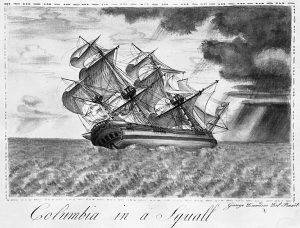

George Davidson sketch, “Columbia in a Squall”

In 1792, an American captain named Robert Gray finally discovered the mouth, crossed the bar and sailed 13 miles up the river, thereby naming it after his ship, Columbia Rediviva. He also named a small tributary after himself (Gray’s River). Later that same year, the Royal Navy’s Lieutenant Broughton made it a bit further up river, navigating through the coast range and reaching the west end of the Gorge where he sighted and named Mount Hood.

Discover the history of the NW Rivers with Todd Weber (Historian) on the American Pride or American Song!!

Lewis and Clark:

Northwest natives encountered many foreigners in the 18th and 19th centuries, but the most notable were, of course, American explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. As they traversed the American West between 1803 and 1805, Lewis and Clark crossed the Rocky Mountains and found no NW passage. With the help of Sacagawea, a native woman who’d assisted them since the Dakota region, they eventually entered “Oregon Country” via canoe. They paddling down the Snake River and reached the Columbia near what is now Tri-Cities, Washington. They took the river west, often trading goods in return for help from natives until they reached the Pacific.

In 1811, Canadian explorer David Thompson traveled from present-day Invermere, B.C. all the way to the Pacific, becoming the first European-American to tour the entire length of the Columbia.

Colonization along the Columbia River:

The American-owned Pacific Fur Company founded Astoria in 1811, and Britain’s Hudson Bay Company established Fort Vancouver in 1825. This led to a joint-occupation of the river basin between the U.S and Britain. As Fort Vancouver became a major trading post, the British dominated the region until American missionaries reached the lower Columbia in the 1830s, and a mass migration of American settlers arrived via Oregon Trail in the 1840s.

To recapture a strong hold on Oregon Country, the Hudson Bay Company shifted from the declining fur trade to salmon and lumber, and the British launched a few colonization schemes. But by then the Americans heavily outnumbered them, spreading south into the Willamette Valley. This rekindled joint-occupation and boundary disputes, so in 1846, the Oregon Treaty effectively set boundary lines at the 49th parallel (near what eventually became the Canadian border). Oregon became a U.S. state in 1859, and Washington in 1889 with the Columbia River acting as the border between them.

To recapture a strong hold on Oregon Country, the Hudson Bay Company shifted from the declining fur trade to salmon and lumber, and the British launched a few colonization schemes. But by then the Americans heavily outnumbered them, spreading south into the Willamette Valley. This rekindled joint-occupation and boundary disputes, so in 1846, the Oregon Treaty effectively set boundary lines at the 49th parallel (near what eventually became the Canadian border). Oregon became a U.S. state in 1859, and Washington in 1889 with the Columbia River acting as the border between them.

As for the natives, a significant number were wiped out by smallpox when explorers worked their way in from the coast and began trading. Then, as the region was overtaken by Americans, more illnesses spread throughout native tribes and tensions mounted. The Cayuse and Umatilla accused Dr. Marcus Whitman of poisoning natives in his care, then killed Whitman along with his wife and 11 others, which is now known as the Whitman massacre or Walla Walla massacre. This event was the pinnacle conflict between natives and the Whitman’s, who had arrived in the first wagon train along the Oregon Trail.

Many battles broke out after the massacre and the natives’ fishing rights became restricted. Commercial fish canneries were established by settlers, severely depleting the salmon population and driving away many of the remaining tribes. However, some of them were able to save their fishing rights by negotiating treaties with the U.S government. As river development pressed on in the 1900s, major changes were made in order to improve shipping navigability.

Early Navigation on the Columbia River:

Throughout the last century (and then some) many changes have been made the Columbia River to improve its navigability. These changes have included jetties, dams, dredging, canals, and locks. Thanks to these alterations, ocean freighters are able to reach Portland, and our cruise ships can go as far as Clarkston, WA along the Snake River.

As they say, however, necessity is the mother of invention. All of these changes came about after years of restricted travel due to rocky rapids, shallow channels, and a treacherous sandbar at the mouth of the river.

At first, steamboats and other vessels operated exclusively along the lower Columbia between the Pacific Ocean and the Cascade Rapids. This stretch was referred to as the “lower river.” Ships could also travel along the Willamette River, reaching Portland and Oregon City. The Cascade Rapids blocked boats from being able to reach the middle Columbia, which stretched from there through the Gorge to another impediment, Celilo Falls.

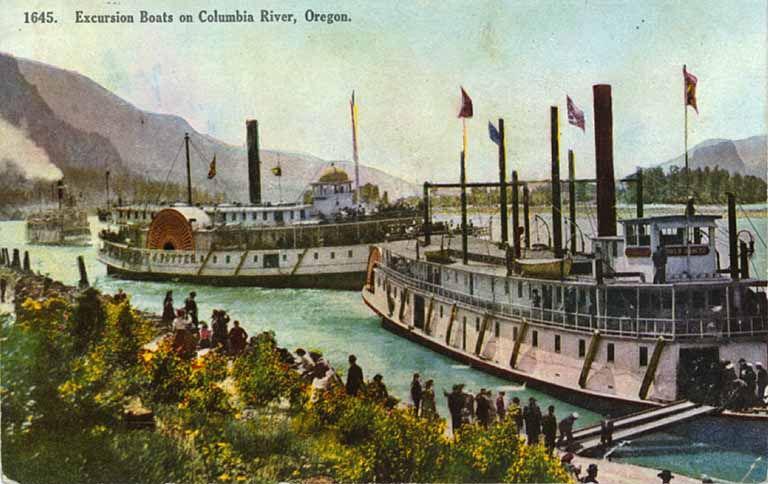

1910 Steamboats on the Columbia River

The Middle:

In 1850, a mule-drawn railway was built around the Cascade Rapids on the north side of the river. It was used to winch a new steamboat along the bank to circumvent the rapids and operate on the middle stretch. Unfortunately, it was ahead of its time, and business didn’t support having a steamboat on the middle Columbia just yet. So, the boat was winched back down to the lower river. The next steamboat to reach the middle was hauled up over the rapids in 1853. By then business had increased, so a second boat was brought across and another mule-hauled rail was built on the south bank of the river in 1858.

The Upper:

The next task was to take a boat beyond Celilo Falls and operate along the upper Columbia to what is now Walla Walla County and the Snake River. The first steamboat built for this purpose was constructed near the Cascades, but unfortunately, she was swept over the rapids upon launching and hit a rock on the way down. The first steamboat to operate on the upper Columbia was built at the mouth of the Deschutes River in 1858, and another began operation in 1860. Both were exceedingly profitable. Later, the Oregon Steam Navigation Company built a portage railroad that ran on the river bank between Celilo and the Dalles. The steamboats carried passengers and cargo throughout the upper, middle, and lower Columbia for many years. But in the 1880s, railroads began supplementing steamboat operations, linking transportation along the full stretch of the river between the Pacific and Lewiston, ID. Traveling by rail proved to be far less expensive and soon the steamboats were losing business.

Canals and Locks on the Columbia River:

The Dalles OR Celilo Canal Construction

Frustrated, shippers and steamboat lines urged Congress to fund improvements to the river that would help them compete with the railroads. The two main improvement projects were the Cascade Locks and Canal, completed in 1896, and the Celilo Canal and Locks, completed in 1915. While this did open the river all the way to the Snake, the steamboats would never regain a competitive position against the railroads. Freight shipping through the lower Columbia did remain strong. Navigating through the mouth of the Columbia River had never been easy. A long, narrow, and often shifting sandbar made passage from the Pacific into the river challenging and hazardous. In 1886, jetties were constructed to break unrelenting currents and extend the Columbia’s channel into the ocean. To allow for larger, heavier vessels, the river was dredged in 1891. It was deepened from 17 feet to 25 feet between Portland and the Pacific, and by 1976 it was deepened again to 40 feet. Efforts to maintain and improve navigation of the Columbia River continue to this day.

Between 1850 and 1981 many steamboats operated on the Columbia River and its tributaries, including the Willamette and Snake rivers. Early on, boats were confined to the lower river as the Cascade and Celilo rapids made for formidable obstacles to the middle and upper stretches. However, passengers could reach from Astoria to Portland, Milwaukie and Oregon City, leading to rapid increases in the regional population.

The very first steamboat to arrive was the Beaver, which was constructed in England. She left London in May of 1835 and reached Oregon City in May of 1836. The Beaver served Oregon Country alone for 14 years until the side-wheeler Columbia (not to be confused with the Columbia Rediviva) was christened in Astoria in 1850. On her first run, it took 2 days for the Columbia to travel from Astoria to Portland. This was mostly because her captain was being especially cautious during his first navigation of the river. From then on, Columbia cruised at four miles per hour between Oregon City and Astoria twice a month.

Cruise from Portland to Astoria and beyond aboard the Queen of the West!

Soon after the Columbia, the side-wheeler Lot Whitcomb was shipped in pieces from the East Coast and assembled in Milwaukie. She was larger, more luxurious, and faster than the Columbia (cruising at 12 mph) yet charged the same rates for passengers and freight ($25 per person/ton). Thus, the Lot Whitcomb assumed much of the Columbia’s business.

There were three basic types of steamboats that cruised on the Columbia River: propeller, side-wheeler, and sternwheeler. Because propellers needed an uncommonly deep channel and side-wheelers required a special kind of dock (which was expensive), the sternwheeler emerged as the most popular steamboat construction. Sternwheelers were easier to maneuver and could dock just about anywhere.

Steamboat burned wood for fuel and typically went through 4 cords per hour. Luckily the Pacific Northwest is a highly wooded area. But, as boats reached the middle and upper stretches of the river where there wasn’t much wood, it had to be brought in and accumulated at stops along the route. As you might guess, providing wood for steamboat operations became a vital part of the economy.

Other boats to navigate the Columbia include:

- Belle of Oregon City

- Wallamet

- Multnomah

- James P. Flint (which was winched over the Cascade rapids and then back shortly after. Then in 1852, the Flint struck a rock and sank, but was raised and renamed the Fashion.)

- Allen

- Washington

- Eagle

- Black Hawk

- Hoosier

- Jennie Clark (the first sternwheeler in 1855)

- Mary

- Venture (intended to navigate the upper river but was swept over the Cascade rapids and destroyed)

- Colonel Wright (first to operate on the upper)

- Tenino

In the early 1850s, the fare for passage between Portland and Oregon city on the Eagle was $5 per person and $15 per ton of freight. Those costs increased over the years, particularly during the gold rush, and other fees were included, like meals. Eventually steamboat companies began running price-per-ton schemes for freight and captains became wealthy men. For example, Leonard Wright, captain of the Colonel Wright, earned $500 dollars a month, which was quite a lot for those times.

The Oregon Steam Navigation Company was formed by local owners, captains, and visionaries around 1860 and quickly monopolized the boats on the Columbia and Snake rivers. Almost 20 years later, the group made a significant profit by selling out to the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company (OR&N), which expanded upon the existing monopoly to control all rail and steamboat transport in the region. Once the railways were completed along the river, OR&N brought its boats from other stretches down to the lower river with the intent of forcing patrons to travel by rail. Steam boating all but ceased above The Dalles until 1896 when the Cascade Locks and Canal were finished, allowing easier access to the middle river.

Explore all the highlights of the Columbia River Gorge!

While facing stiff competition with railway travel at the turn of the century, faster and more luxurious steamboats were built, including the Altona and a new Hassalo. The Hassalo cruised at 26 mph, and many claimed it was the fastest steamboat in the world.

Steamboat operations had declined significantly by 1915, even though the locks and canal were finally completed at Celilo falls. The only boats running east of Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River were the Dalles City and Bailey Gatzert (pictured above). A few boats being operated by the Harkins Transportation Company, including a new propeller called Georgiana, navigated downriver to Astoria.

There are only to steamboats that still exist from before 1915, the Moyie (pictured below) and Sicamous, which are both passenger-carrying sternwheelers. Unfortunately, no side-wheelers survived. These two boats are kept out of water and have been preserved but are not operational. Moyie is considered by many to be the oldest surviving vessel of her kind.

Moyie is considered by many to be the oldest surviving vessel of her kind.

Cruise the Columbia River and follow the path of the original steamboats of Oregon Country! Contact USA River Cruises today– these trips book up fast! Use our simple contact form or call 1-866-626-6544.